Bassiani

OCTOBER 2021

Bassiani was founded as both an international techno club and social movement, bringing together those who have been oppressed by dominant culture and intolerant social norms in Georgia and the rest of the South Caucasus. Through the unifying force of electronic music, Bassiani works with like-minded groups to abolish social, legal and political discrimination - primarily regarding anti LGBTQI+ sentiment and disproportionately harsh drug laws. Recently, efforts to save Tbilisi’s club culture and techno scene have been at the forefront of Bassiani’s activities. Their vision is based on four main values: solidarity, equality, responsibility and education.

“On this day, we realized we were facing very big problems and that we actually didn’t have such a big community. We realized that we needed this space to create this community of like-minded people to unite. We realized that every social group like the queer people, the woman, the labor workers were all kind of abandoned and fighting in their own ways.”

Discrimination against the LGBTQI+ community

Despite the numerous attempts by the social movements, activists and organisations over the last two decades to move Georgia in a more tolerant direction, popular sentiment has stagnated and severe discrimination against the LGBTQI+ community persists. Since 2013, the 17th of May has been recognized as one of the most significant days for the community: the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia (IDAHOT). On that date in 2013, a group of around 50 LGBTQI+ activists were violently attacked by thousands of protesters led by Georgian Orthodox priests. The following year, the Orthodox Church designated the 17th of May “Family Purity Day” in an attempt to solidify the primacy of heteronormative values. Since then, the patriarchate, religious conservatives and far-right groups have appropriated the day to march in opposition to Georgia’s pro LGBTQI+ movement.

In 2018, IDAHOT was forced to have organizers cancel or reschedule their 17th of May demonstrations until adequate safety measures were employed by the government. But seeking protection in a society that continues to marginalize and oppress alternative communities has been futile. According to a June 2018 poll by the National Democratic Institute, only 23% percent of the Georgian population was in support of protecting the rights of sexual minorities. In 2019, IDAHOT was silenced once again, choosing to avoid demonstrating in the streets on 17 May, instead hanging a rainbow flag from Baratashvili Bridge in the center of the city.

However, according to public opinion research conducted by Edison Research and published in September 2021, 73% of Georgia’s population reported that they think the state should have protected the safety of Tbilisi Pride, organized in July 2021. This marks a very important and unexpected shift in public opinion. There is hope, following a July 2021 protest against homophobia in Tbilisi. Thousands rallied to denounce attacks on the LGBTQI+ community that had forced activists to cancel a planned Pride march, yet again.

The Zero Tolerance policy was introduced in 2006-2007 by then President Mikheil Saakashvili, in an attempt to fight organized crime, including drug-related offenses. But many of the people targeted were not part of crime syndicates and incarceration rates in Georgia skyrocketed. Both use and possession carried the same risks, as the law didn’t distinguish between small, large and extra large quantities for 160 of 228 scheduled narcotics. In 2015 a Council of Europe (COE) survey showed that more than 25% of all inmates in Georgia (2,721 of 10,242) were serving time on drug-related crimes.

In 2018, Minister of Internal Affairs Giorgi Gakharia promised to re-exam Georgia’s drug policy, but it wasn’t until February 2021 when the parliament finally passed a bill that defined the legal severity of possessing certain drugs and at what quantities. The lengthy process for changing laws and regulations related to social issues in Georgia continues largely because of the influence and widespread support for the Georgian Orthodox Church.

“When we came to the arena to see it for ourselves, even though it was full of garbage, it was obvious for us that this would be the place of our club. We removed 20 tons of garbage with our own hands.”

Origins

Bassiani was officially founded in 2014, when the club moved to its current location in an abandoned swimming pool basin under the soviet stadium, Dinamo Arena. For almost a year before that, co-founders Zviad Gelbakhiani, Tato Getia and Naja Orashvili had been organizing the parties at a warehouse near the Kura River. As Bassiani began to outgrow the space along the river, the directors of Dinamo Arena heard they were looking for a new spot, and contacted the collective to check out the abandoned areas unused by the stadium.

In a country conditioned by religious conservatism and rampant discrimination against alternative communities, Bassiani wanted to create a shared safe space to bring together the marginalized groups of Georgia. They saw this as an opportunity for these groups to connect with each other and share their experiences, struggles and love of techno. From this, a stronger, united movement could emerge.

Use of the space

Bassiani has an inclusive door policy, giving the space to many different social groups. But the community mainly consists of alternative and creative individuals, women, LGBTQI+ and other groups that continue to experience social inequality. In recent years, the community has organically grown to include more and more young people from the South Caucasus.

By uniting like-minded communities and individuals who are challenging systemic and social inequality within Georgia, Bassiani lays the groundwork for building an effective resistance. It’s not only a club, but also a movement. Similar to the concept of an “Agora,” Bassiani’s space is used as a community gathering point for social, artistic and political activities, including:

- Weekly club nights

- Monthly queer nights (Horoom)

- Gatherings of emerging social movements

- Regular meetings of the White Noise Movement

- Live concerts of LGBTQI+ musicians

- Movie screenings

- Queer art and fashion shows

Image: Horoom nights. Photo credit: Nia Gvatua

From raids to #raveolution

On 12 May 2018 at 1:00am, a large-scale police operation was launched at Bassiani and Cafe Gallery (another prominent space in Tbilisi’s club scene). Police entered the clubs, allegedly searching for drugs, though some reported drugs actually being planted on guests. Regardless, the amount of force that police used during the raid was extreme.

Image: 12 May 2018. Source: Bassiani

Gigi Jikia aka HVL, one of Bassiani’s resident DJs, remembers the night very well:

“I was playing an opening set for Giegling label night at Bassiani. Around 1am I saw the flash lights approaching from across the room. At first I thought it was someone taking videos with their phone, but then they came closer and I saw automatic rifles pointed at me, then heard men in soldier uniforms screaming to stop the music and turn the lights on.”

As citizens were forced outside, a spontaneous rally against the police aggression erupted, later moving 3.6km to the area outside of the parliament building. There, law enforcement continued to show their force by placing people under arbitrary arrest. Among the over 40 detainees were the co-founders of Bassiani and activists of the White Noise Movement.

The police raid and the tactics used to separate protesting crowds represented a violation of the right to peaceful assembly. In July 2018, the Human Rights Education and Monitoring Center (EMC) and the Georgian Young Lawyers Association (GYLA) presented a joint report that found the search warrant the Ministry of Internal Affairs obtained from Tbilisi City Court was abstract and unspecific, with no clear definition of what the police intended to seize upon entering the clubs.

Video: Raid on Bassiani, 12 May 2018. Source: Bassiani

According to a coalition of international human rights organizations, the police operations of 12 May were an aggressive display of the “government’s repressive machinery,” and a targeted set of “micro special operations” to arrest political/civil rights activists and peaceful citizens. It likely had little to do with drugs, but rather silencing Georgian’s who didn’t fit within the conservative status quo.

The 12 May 2018 raid set in motion a well-organized reaction from Georgia’s alternative and marginalized communities, deemed the “raveolution.” Over the coming months, the protests drew global attention for their unique melding of sociopolitical issues and electronic music. The party had become political.

Video: Footage of rave in front of the Parliament building, May 2018. Source: Bassiani

Solidarity

When Bassiani was raided on 12 May 2018, it took almost no time for hundreds and then thousands of people to join the club-goers in defending Bassiani. It was all self-organized. The urgency was so big in people’s minds, that they knew instinctively how to act as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Bassiani has changed the lives of thousands of people in Georgia, providing space for communities and individuals who have experienced hatred, discrimination and aggression just for being themselves. But it’s not only a physical shelter. Bassiani’s formation was also an act of solidarity, bringing together like-minded groups so they could organize and fight the oppression they had grown so tired of.

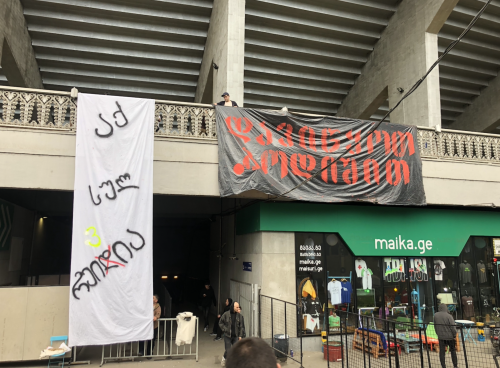

Image: Protests after raid Bassiani, May 2018. Source: Bassiani

We dance together, we fight together

On the afternoon of 12 May 2018, the protests continued, but with greater magnitude. Around 3:00pm, protestors set up a sound system on the steps of Georgian Parliament. DJs from a Bassiani party the preceding Friday played, while the crowd reached the thousands.

Those who had danced in the clubs to find freedom, now poured into Tbilisi’s city center, turning the steps of the parliament into their dance floor. “We dance together, we fight together” was the slogan. What was transpiring wasn’t a typical protest – there was love, peace and a steadfast, unified opposition against intolerance institutionalized aggression – all while people moved and sweated to the music.

Even without the physical space of the club, Bassiani as a social movement carried its values of solidarity, equality and freedom to the streets. By midnight on the first day, protestors were pitching tents in the rain, preparing to spend the night and return to dance the following morning.

The outcome of the peaceful two-day rally was an apology from Minister of Internal Affairs Giorgi Gakharia and his promisethat the current drug policy would be reviewed. Bassiani would reopen after several weeks. And in July 2018, the Constitutional Court of Georgia released a statement on the decision to effectively abolish administrative punishment for the use of marijuana.

REGIONAL INFLUENCE

In addition to bringing Georgians together, Bassiani has also become a space for uniting people and movements from neighboring countries. Even with the struggles alternative communities in Georgia face, Tbilisi has been a bit of a haven in a region wrought with conflict and repression – from Armenia and Azerbaijan, to Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Iran. People from these countries started coming to Bassiani, interacting and forming friendships with each other. Upon returning home, they realized the power of having such a space and community, many starting techno clubs in their own cities.

Even more importantly, the mixing of nationalities and the formation of personal connections based on a shared love of music, introduced the possibility of peace and reconciliation in regional conflicts. During the first Boiler Room party in Armenia in March 2019, one of the DJs wore a shirt reading “Music has no enemies. Baku, Yerevan are friends. The Earth is our home.” This caused a huge discussion in Azerbaijan and Armenia about the need for solidarity between the two countries. Not everyone agreed with the message, but at least a discussion had started and the narrative was shifting.

“So what we did was invite people on social groups and platforms for communities and organizations to dance with us and dance with each other and to create a social network of all these people. Yeah, and that’s how we started to go as the Dance Floor Activists.”

THE POWER OF SYMBOLISM

Bassiani strategically communicates with potent visual elements and collective memory. The Battle of Basian was one of the biggest battles in the history of Georgia, remembered by Georgians as a tale of victory and freedom. The club was named after this 13th century fight against the Seljuk Empire led by Georgia’s first female ruler, because the co-founders knew that Bassiani would be fighting a present-day battle for freedom and equality. Also, in Georgian Bassiani literally means “the one with bass” – so the second “s” was added in the name to create the connection with techno music.

Bassiani’s logo is a helmet that brings together two types of armour: Roman and Asian. This represents Georgia’s place at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, and the cultural influences from East and West, Muslim and Christian. The logo also alludes to the movement’s unifying role in mobilizing different segments of Georgian society for a shared cause. In a short animated video released by Bassiani during the club’s early years, the power of a unified community battling a common “enemy” through music and dance is evident.

BUILDING A NETWORK OF COMMUNITIES

From the beginning, Bassiani’s co-founders knew that in order to create a strong community, they needed to include different social groups – from women and LGBTQI+ community members, to and policy-makers activists, musicians, visual artists and designers. Using dance as a basis for unity, the club launched by inviting people to join via community platforms and organizations. By creating these solidarity-based networks, with individuals acting as “dancefloor activists,” the government’s attempts to rule the masses were significantly challenged. The possibility to “divide and conquer ” Georgia’s marginalized communities was waning.

UNIQUE FORM OF PROTEST

The protests that started the day after the May 2018 raid of Bassiani were anything but typical, as a unified opposition danced against the government and widespread conservatism. Everybody knew there would be a protest, but no one expected one quite like that. It turned out that taking something as ubiquitous and seemingly apolitical as music and dance created an environment that welcomed a wide range of protestors and movements. The “techno protests” garnered international attention, largely due to a unique approach to collective action and the network of DJs, clubs and supporters that Bassiani has throughout the electronic music scene.

COMMUNICATIONS STRATEGY

The protests continued for days, not only attracting attention from international media, but also acts of solidarity from a large group of international musicians and other influential allies. Over the years, Bassiani had gathered an extensive alliance of international supporters that now used their voice to condemn the actions of the Georgian government. Campaigns were initiated in Berlin and other European cities, and the slogan “we dance together, we fight together” became widely used among DJs and artists in their support of Bassiani.

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

While challenging the system from the outside is critical, so is working within the legal framework if possible. Bassiani has been collaborating with the harm-reduction group, White Noise Movement, and other human rights associations aiming to change Georgia’s extreme drug policy. The coalition has been filing cases with Georgia’s Constitutional Court for people imprisoned on charges of suspected drug use. By winning these cases, a legal precedent is set for similar cases, which has in turn led to the release of thousands of people from prison. The same team has been working with politicians to overturn the harsh drug laws, drafting legislation to be presented to Parliament.

CULTURAL AND CREATIVE INDUSTRIES UNION OF GEORGIA (CCIU)

It still wasn’t enough to keep Tbilisi’s club scene alive though, and by December 2021 CCIU decided to turn to the government. Utilizing a practical, comprehensive and collaborative guide from VibeLab for “reactivating nighttime economies and cultures” – aptly named the Global Nighttime Recovery Plan – CCIU not only sent an appeal to the Tbilisi government, but an entire plan of action. The proposal also contextualized the need and “explained how the electronic music ecosystem works…” including “…all of the possible beneficiaries,” Lezhava told VibeLabs’ nighttime.org.

CCIU’s lobbying worked. On 1 March 2021, 2 million GEL (503,000 EUR) from the Tbilisi Municipality Reserve Fund was designated to support electronic music and club culture in the city. To oversee the allocation of the grant money, Orashvili and Lezhava launched the act4culture.com platform where clubs, artists, bars, DJ schools, radio stations, record shops, labels, artist agencies, festivals, etc. can apply for funding.

Recently CCIU initiated and implemented the #OpenCulture project, conducting two pilot nights in cooperation with the city’s Municipality and medical lab to research the spread of Covid-19 both at the outdoor and indoor spaces while the certain safety measures are proposed. In frames of #OpenCulture, only fully vaccinated, covid-free (in the last six months) and those with PCR test’s negative results are allowed to enter the space. The research results seem promising and this lays a groundwork to finally opening the clubs, bars, festivals and all other outdoor or indoor spaces which had been closed since the pandemic began.

STRONG PRINCIPLES

It’s pretty clear that Bassiani adheres closely to its core principles, doing everything they can to provide Tbilisi with an inclusive and safe space to come together and dance – even when things become challenging. Aside from the aggression by police, an example is a recent mass shooting in front of the entrance of the club. One person shot 16 bullets, injuring several people (no one died). But Bassiani kept their doors open because they know that the dance floor is where people learn new values and new ways of working together to apply them. This kind of informal education has the capacity to go beyond the club scene and hopefully one day permeate Georgian society more broadly.

Video: Excerpt from “Dance or Die”. Video credit: Naja Orashvili and Giorgi Kikonishvili

SAVING CLUB CULTURE IN A PANDEMIC

As in other cities across the world, Bassiani and Tbilisi’s club scene in general have faced bankruptcy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Considered linchpins of progressive society and cultural expression, clubs have had to face the fact that popular support isn’t enough to weather national lockdowns. Some cities already had organized commissions, associations, collectives, etc., meant to protect the interests of clubs and lobby municipalities, when the lockdowns started in 2020. Others, like Tbilisi, did not.

It’s not surprising then, that Bassiani co-founder and owner Naja Orashvili, along with David Lezhava, decided to mobilize industry stakeholders and form the non-profit NGO, Cultural and Creative Industries Union of Georgia (CCIU). With no revenue or government aid reaching the clubs or creative industries, the association’s first step was to go to the fans – by establishing a Tbilisi branch of the Berlin-based initiative United We Stream. Livestreaming sets from what were now empty clubs, UWS Tbilisi was able to initially raise around 30,000 GEL (roughly 7,500 EUR) to support local artists and venues.

RCONNEXTION

Orashvili and Kikonishvili, both representing Bassiani and Horoom Nights, recently teamed up with local artists, publishers and researchers to establish a new collective Spectrum and likewise unite alongside with the queer artists collective Fungus, all under the umbrella name Rconnextion.

Rconnextion helps regenerate and revitalize the diffused structure of social and artistic life by combining art and science, academia and interdisciplinary activities. The aim is to study, analyze and elaborate on the currents of queer sexuality, emotions, politics and social life and to incite knowledge-based public discussions on topics that are thoroughly hidden behind heteronormative culture. Interdisciplinary thinkers, artists and activists come together to ask the questions that aren’t being asked and to answer them. In addition, Rconnextion seeks to not only transform unequal, homophobic and sexist social norms, but also instigate the spread of queer/feminist perspectives within public life through the arts and academic sciences.

“From the very first second when I entered the club, I had this feeling of not being in Georgia at all. The biggest thing that really shook me was how the people related and how people interacted with each other. There was very empathy based, very friendly, very caring interaction between people, even between strangers. It was nothing I have ever experienced during the daytime in social interactions in Georgia.”